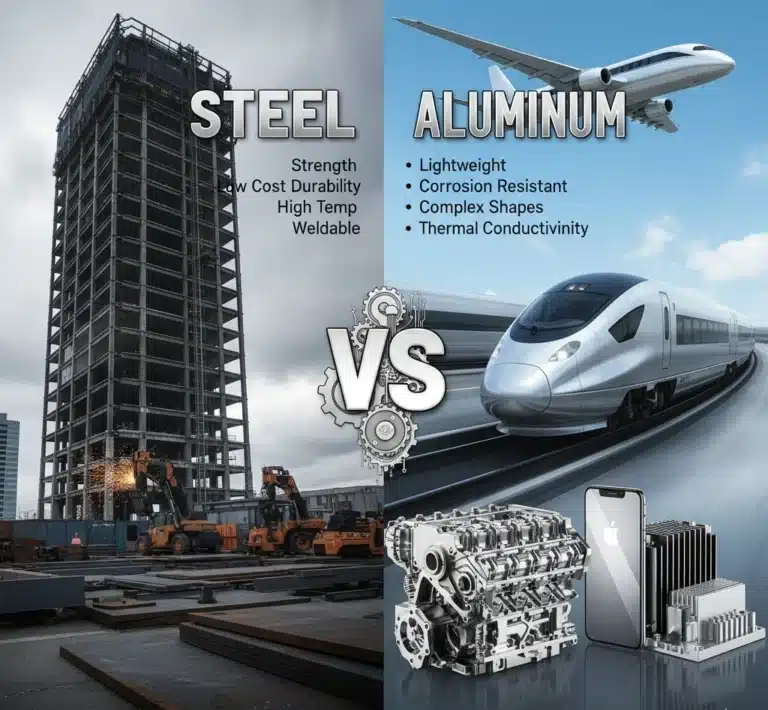

Choosing the right material is one of the most critical decisions an engineer or product designer can make. It impacts performance, cost, durability, and the manufacturing process itself. Two of the most common and versatile materials in modern manufacturing are steel vs aluminum. While both are ubiquitous, they offer vastly different properties. So, how do you decide between the unyielding strength of steel and the lightweight versatility of aluminum?

This guide will provide a comprehensive comparison to help you make an informed decision. We’ll explore their history, core properties, processing differences, and application-specific advantages to determine which metal is the optimal choice for your next project.

- Key Takeaways

- Steel vs Aluminum: Historical Context and Production Landscape

- Core Material Properties: Steel's Strength vs. Aluminum's Weight

- Fabrication and Processing Differences

- Surface Treatment and Finishing

- Common Applications: Where Each Metal Shines

- Conclusion: How to Choose the Right Material for Your Project: Steel vs Aluminum

- Let CastMold Guide Your Decision

- Aluminum Die Casting Services

Key Takeaways

- Strength/Stiffness Critical (Space-Constrained): When the primary requirement is to handle maximum load in the smallest possible cross-section, steel is the clear choice. Its high modulus of elasticity and tensile strength are indispensable.

- Examples: Structural beams in buildings, heavy machinery frames, landing gear.

- Weight Critical (Performance/Efficiency Driven): When reducing mass is the top priority to improve speed, fuel efficiency, or payload capacity, aluminum is the superior option due to its excellent strength-to-weight ratio.

- Examples: Aircraft structures, high-performance automotive bodies, lightweight consumer electronics.

- Initial Cost Critical (Bulk/Mass Market): For applications where minimizing upfront capital expenditure is the main goal and other properties are secondary, carbon steel is almost always the most economical material.

- Examples: Concrete reinforcement bars (rebar), basic structural components, low-cost consumer goods.

- Lifecycle Cost/Corrosion Critical (Long-Life/Harsh Environment): For assets with a long expected service life, especially in corrosive environments, the lower maintenance and higher durability of aluminum or stainless steel often justify a higher initial cost.

- Examples: Marine vessels, architectural facades, bridges in coastal areas, transportation fleets.

- Thermal/Electrical Conductivity Critical: For applications requiring efficient transfer of heat or electricity, aluminum is the definitive choice over steel.

- Examples: Electrical heat sinks, power transmission lines, heat exchangers.

- High-Cycle Fatigue Critical: For components subjected to millions of small, repeated stress cycles where failure is not an option, steel‘s endurance limit provides a unique safety and reliability advantage.

- Examples: Engine crankshafts, rotating shafts in industrial equipment, springs.

Steel vs Aluminum: Historical Context and Production Landscape

- Steel: The Backbone of the Industrial Revolution. Steel, an alloy of iron and carbon, has been produced in small amounts for centuries, but its mass production began in the mid-19th century with the invention of the Bessemer process. This innovation drastically lowered its cost, making it the primary material for railways, skyscrapers, bridges, and heavy machinery, fundamentally building the modern world.

- Aluminum: The Metal of the Modern Age. For a long time, aluminum was more valuable than gold because it was incredibly difficult to refine. That changed in 1886 with the development of the Hall-Héroult process, which made industrial-scale production feasible. Its defining moment came with the dawn of aviation, where its low weight was essential for flight, cementing its status as a high-performance, modern material.

Global Production Footprint: A Comparative Analysis

Steel Supply Chain: The production of steel begins with the mining of iron ore. Global production is dominated by a few key players, with Australia and Brazil together accounting for the majority of the world’s iron ore exports. Other significant producers include China and India. This raw material is then converted into crude steel. Here, the landscape is dominated by a single nation: China. In 2023, the world produced nearly 1.9 billion tonnes of crude steel, and China alone was responsible for over 1 billion tonnes, or more than 54% of the global total. This is followed by India, Japan, and the United States, whose production volumes are an order of magnitude smaller.

Aluminum Supply Chain: The aluminum supply chain starts with bauxite ore. The world’s largest producers of bauxite are Guinea, Australia, and China. This bauxite is then refined into alumina before being smelted into primary aluminum. Similar to steel, the smelting stage is heavily concentrated in China, which produced over 40 million metric tons in 2022, accounting for nearly 60% of the world’s total primary aluminum output of approximately 69 million metric tons.25 India and Russia are distant second and third-place producers.

This analysis reveals a critical dynamic in global manufacturing: while the raw materials for both metals are geographically dispersed, the energy-intensive processing and refining stages are overwhelmingly concentrated in China. This creates a significant dependency for the rest of the world, making the global supply chains for both steel and aluminum vulnerable to shifts in China’s domestic policies, energy costs, and geopolitical positioning.

| Material | Total World Production | Top 3 Producing Countries (Volume) |

| Iron Ore (Usable) | ~2,500 | 1. Australia (960) 2. Brazil (440) 3. China (280) |

| Bauxite | ~450 | 1. Guinea (130) 2. Australia (100) 3. China (93) |

| Crude Steel | ~1,886 | 1. China (1,005) 2. India (149) 3. Japan (84) |

| Primary Aluminum | ~70 | 1. China (41) 2. India (4.1) 3. Russia (3.8) |

Core Material Properties: Steel’s Strength vs. Aluminum’s Weight

The fundamental choice between steel and aluminum comes down to a trade-off between their distinct properties.

Strength, Stiffness, and Hardness

When it comes to pure strength and rigidity in a given volume, steel is the undisputed winner.

- Absolute Strength: A standard carbon steel can have a tensile strength of 400-550 MPa, while a common aluminum alloy like 6061-T6 is around 310 MPa. High-strength steels can exceed 2000 MPa, whereas the strongest aluminum alloys peak around 570 MPa.

- Stiffness (Modulus of Elasticity): Steel is approximately three times stiffer than aluminum. This means under the same load, an aluminum part will bend or deflect three times as much as an identical steel part.

- Hardness: Steel is significantly harder than aluminum, giving it superior resistance to wear, abrasion, and indentation.

Density and the Strength-to-Weight Ratio

This is where the tables turn. Aluminum’s chief advantage is its low density. It has a density of about 2.7 g/cm³, nearly three times lighter than steel’s 7.85 g/cm³.

Because of this, aluminum possesses a far superior strength-to-weight ratio. While an aluminum part may need to be physically larger to match the stiffness of a steel one, it will only weigh about half as much. This makes aluminum the go-to choice for industries like aerospace and high-performance automotive, where minimizing weight is the top priority.

Thermal and Electrical Characteristics

Steel and aluminum exhibit nearly opposite behaviors regarding the transfer of heat and electricity, making their applications in these domains highly specialized.

- Thermal Conductivity: Aluminum is an excellent conductor of heat, with a thermal conductivity of around 235 W/m·K. Steel, by contrast, is a relatively poor thermal conductor; carbon steel’s conductivity is about 45 W/m·K, and stainless steel’s is even lower at approximately 15 W/m·K. This makes aluminum the ideal choice for applications requiring efficient heat dissipation, such as computer heat sinks, HVAC components, and cookware.

- Heat Resistance: The high thermal conductivity of aluminum is paired with a low melting point of about 660°C (1220°F). It begins to lose a significant portion of its strength at temperatures above 200°C (400°F).Steel has a much higher melting point, typically between 1370°C and 1510°C (2500-2750°F), allowing it to maintain its structural integrity at far higher temperatures.

- Electrical Conductivity: Aluminum is a very good conductor of electricity, with a conductivity rating of about 61% of the International Annealed Copper Standard (IACS). Steel is a poor conductor, with carbon steel rated at only about 12% IACS. Due to its combination of good conductivity, light weight, and lower cost compared to copper, aluminum is widely used for high-voltage electrical transmission lines.

Chemical Resilience: The Science of Corrosion

The way steel and aluminum react with oxygen dictates their long-term durability, especially in outdoor or moist environments.

- Steel’s Vulnerability (Rust): Carbon steel is primarily composed of iron, which reacts with oxygen and moisture to form hydrated iron(III) oxide, commonly known as rust. This reddish-brown layer is brittle, porous, and flakes off, exposing fresh metal underneath to continue the corrosive process. To prevent this, carbon steel almost always requires a protective coating, such as paint, powder coating, or galvanization (a layer of zinc).

- Aluminum’s Self-Protection (Passivation): Aluminum is highly reactive with oxygen, but this reactivity is its greatest defense. When exposed to air, it instantly forms a very thin, hard, and transparent layer of aluminum oxide on its surface. Unlike rust, this oxide layer is dense, non-porous, and strongly bonded to the parent metal. It acts as a protective “passivation” layer, sealing the aluminum from further contact with the environment and preventing corrosion. If the surface is scratched, a new protective layer forms immediately. This inherent property makes aluminum exceptionally resistant to corrosion, particularly in marine environments where saltwater would quickly degrade unprotected steel.

- Stainless Steel: This special class of steel is an exception. By alloying steel with a minimum of 10.5% chromium, a passive layer of chromium oxide forms on the surface, which functions similarly to the aluminum oxide layer, providing excellent corrosion resistance. In certain aggressive chemical environments, specific grades of stainless steel can even outperform aluminum.

| Property | Unit | Mild Steel (A36) | Stainless Steel (304) | Aluminum (6061-T6) | High-Strength Aluminum (7075-T6) |

| Density | ~7.85 | ~8.0 | 2.70 | 2.81 | |

| Ultimate Tensile Strength (UTS) | 400–550 | ~515 | ~310 | ~572 | |

| Yield Strength | ~250 | ~205 | ~276 | ~503 | |

| Modulus of Elasticity (Stiffness) | ~200 | ~193 | ~69 | ~72 | |

| Hardness | Brinell (HB) | ~140 | ~123 | ~95 | ~150 |

| Melting Point (Approx.) | °C (°F) | 1420–1540 (2600–2800) | 1400–1450 (2550–2650) | 582–652 (1080–1205) | 477–635 (890–1175) |

| Thermal Conductivity | ~50 | ~16 | ~170 | ~130 | |

| Electrical Conductivity | % IACS | ~12 | ~2.5 | ~43 | ~33 |

| Fatigue Limit | – | Yes | Yes (Generally) | No | No |

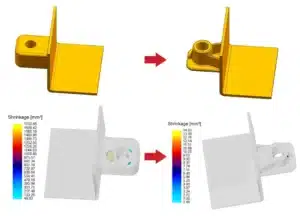

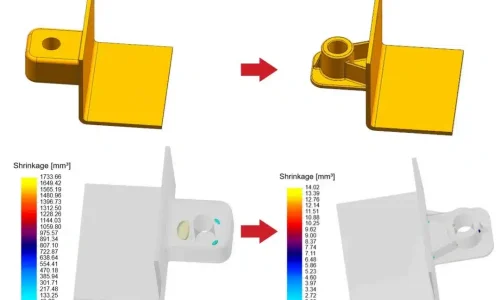

Fabrication and Processing Differences

The inherent properties of steel and aluminum dictate how they are best worked and shaped. At CastMold, we understand how to leverage these differences to optimize your design for manufacturing.

- Casting: Aluminum’s low melting point makes it far easier and less energy-intensive to cast. This makes it perfectly suited for high-pressure die casting, a process that produces complex, near-net-shape parts with excellent precision and finish—something generally not feasible for steel.

- Machining: As mentioned, aluminum is significantly easier to machine than steel. This allows for faster production times, lower costs, and less tool wear, a key consideration for our CNC machining services.

- Extrusion: Aluminum is the ideal material for extrusion, a process of pushing metal through a die to create complex cross-sectional profiles. Its malleability allows for intricate, thin-walled shapes that would be impossible or prohibitively expensive to produce in steel.

- Welding: Steel is generally easier and more forgiving to weld. Welding aluminum is a more specialized skill requiring different equipment (AC TIG) and meticulous cleaning to deal with its protective oxide layer and high thermal conductivity.

| Processing Method | Factor | Steel | Aluminum | Key Considerations |

| Machining | Ease/Speed | Fair to Poor | Excellent | Aluminum can be machined 3-10x faster, reducing time and cost. |

| Welding | Ease/Skill | Excellent | Fair to Poor | Aluminum requires specialized equipment (AC TIG), meticulous cleaning, and higher skill due to oxide layer and thermal conductivity. |

| Casting | Ease/Cost | Fair to Poor | Excellent | Aluminum’s low melting point reduces energy costs and allows for more versatile casting methods like high-pressure die casting. |

| Forging | Resulting Strength | Excellent | Good | Forging enhances both, but forged steel achieves the highest levels of strength and toughness. |

| Extrusion | Complexity/Cost | Poor | Excellent | Aluminum is ideal for creating complex, thin-walled profiles at low toling cost; steel is limited to simple shapes. |

| Bending/Rolling | Process Control | Good | Fair | Steel requires more force but has less springback. Aluminum is easier to bend but its high springback requires precise (often CNC) control. |

Surface Treatment and Finishing

The final finish of a part enhances its durability and aesthetics. The best method depends on the material.

- For Both Metals: Painting and powder coating are effective for both steel and aluminum. Powder coating provides a thick, durable, and uniform finish that is more resistant to chipping and scratching than conventional paint.

- Steel-Specific: Galvanizing. This process involves coating steel with a protective layer of zinc to prevent rust. It offers robust, long-lasting sacrificial protection, making it ideal for industrial and outdoor applications.

- Aluminum-Specific: Anodizing. This is an electrochemical process that thickens aluminum’s natural oxide layer. Anodizing dramatically improves hardness and wear resistance and allows the surface to be dyed in a wide variety of vibrant, metallic colors that won’t chip or peel. At CastMold, we offer a full range of surface finishing options to meet your project’s exact specifications.

| Treatment | Process Summary | Primary Purpose | Suitable Metal(s) | Durability | Aesthetics |

| Painting | Application of liquid paint, often sprayed. | Corrosion protection, color. | Steel, Aluminum | Fair to Good | Excellent color variety, but can show runs or strokes. |

| Powder Coating | Electrostatic application of dry powder, then heat cured. | Corrosion/wear resistance, color. | Steel, Aluminum | Excellent; highly resistant to chipping and scratching. | Excellent; uniform, smooth finish in various textures. |

| Galvanizing | Coating with a layer of zinc, typically via hot-dipping. | Superior rust protection for steel. | Steel, Iron | Excellent; provides sacrificial protection.86 | Limited; rugged, industrial gray/silver finish. |

| Anodizing | Electrochemical thickening of the natural oxide layer. | Corrosion/wear resistance, color. | Aluminum, Titanium | Excellent; hard, integrated surface that won’t peel. | Excellent; wide range of colors with a metallic luster. |

| Plating | Depositing a thin layer of another metal. | Decorative finish, wear resistance, conductivity. | Steel, Aluminum | Good to Excellent | Varies with plated metal (e.g., chrome, gold). |

| Abrasive Blasting | Propelling abrasive media at high pressure. | Surface cleaning and preparation. | Steel, Aluminum | N/A (pre-treatment) | Creates matte or satin textures. |

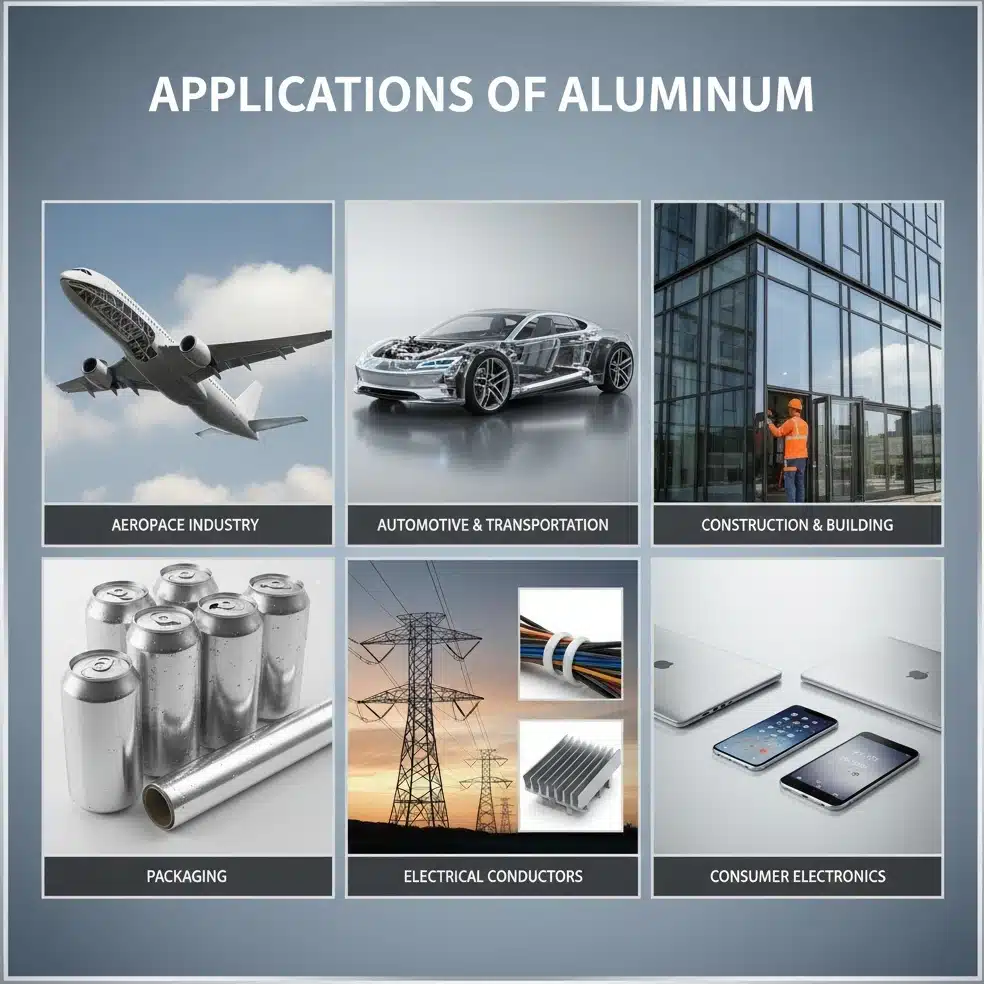

Common Applications: Where Each Metal Shines

The choice between steel and aluminum is often dictated by industry standards and primary performance drivers.

- Construction & Infrastructure: This is steel’s domain. Its immense strength, stiffness, and low cost make it the unparalleled choice for the structural skeletons of buildings, bridges, and heavy machinery. Aluminum is used for non-structural elements like window frames, roofing, and facades where its light weight and corrosion resistance are key.

- Aerospace: This is aluminum’s kingdom. Its high strength-to-weight ratio is the single most critical factor for aircraft construction. Steel is used only in specific, high-stress areas like landing gear and engine mounts where its absolute strength is indispensable.

- Automotive: This is the primary battleground. Steel has long been the incumbent due to its low cost and high strength for crash safety. However, the push for fuel efficiency and electric vehicle range has made lightweighting a top priority, leading to increased use of aluminum for body panels, engine blocks, and entire vehicle structures.

- Consumer Goods & Electronics: Steel is used for durable appliances and tools. Aluminum is favored for premium electronics like laptops and smartphones, where it provides a lightweight, high-end feel and helps dissipate heat.

Conclusion: How to Choose the Right Material for Your Project: Steel vs Aluminum

There is no single “best” material. The optimal choice depends entirely on your project’s primary goal.

Choose Steel when your primary driver is:

- Absolute Strength & Stiffness: For load-bearing applications in a limited space.

- Lowest Initial Cost: When upfront budget is the main constraint.

- High-Temperature Resistance: For parts operating in extreme heat.

- High-Cycle Fatigue Life: For components needing to withstand millions of stress cycles.

Choose Aluminum when your primary driver is:

- Light Weight: When reducing mass to improve efficiency or performance is critical.

- Corrosion Resistance: For parts used in outdoor or marine environments.

- Complex Shapes: When the design requires intricate profiles best made by die casting or extrusion.

- Thermal Conductivity: When you need to efficiently dissipate heat.

Use the comparison table as a quick decision checklist.

| Selection Criterion | Steel | Aluminum |

| Absolute Strength & Hardness | Excellent: Unmatched strength, hardness, and wear resistance by volume. | Fair to Good: Softer and weaker by volume, but high-strength alloys are competitive with mild steels. |

| Strength-to-Weight Ratio | Good: AHSS grades are highly competitive. | Excellent: The defining advantage, providing more strength per unit of mass. |

| Stiffness (Resistance to Bending) | Excellent: Approximately 3x stiffer than aluminum. The choice for rigidity. | Poor: Deflects significantly more under the same load, requiring larger geometries to compensate. |

| Initial Material Cost | Excellent (Carbon Steel): Generally the most affordable structural metal per kilogram. Fair (Stainless Steel): Can be more expensive than aluminum. | Fair: More expensive per kilogram than carbon steel, but lower density narrows the gap for a given volume. |

| Lifecycle Cost (TCO) | Fair: Can be high due to maintenance (rust) and higher operational costs in transport. | Excellent: Often lower over the product life due to minimal maintenance, operational savings (fuel), and high scrap value. |

| Corrosion Resistance | Poor (Carbon Steel): Requires protective coatings. Excellent (Stainless Steel): Passive layer provides superior protection. | Excellent: Natural self-protecting oxide layer prevents rust and provides long-term durability. |

| Machinability | Fair to Poor: Harder material leads to slower machining speeds and higher tool wear. | Excellent: Soft and easy to cut, enabling faster production and lower machining costs. |

| Weldability | Excellent: Forgiving process, requires less specialized equipment and skill. | Fair to Poor: Challenging due to oxide layer, high thermal conductivity, and porosity risk. |

| Formability (esp. Extrusion) | Fair: Requires more force; extrusion is limited to simple shapes. | Excellent: Highly malleable and ideal for extruding complex, intricate profiles. |

| Fatigue Resistance | Excellent: Possesses a fatigue limit, enabling design for “infinite life” in high-cycle applications. | Poor: Has no fatigue limit; must be designed for a finite service life with scheduled inspections. |

| High-Temperature Performance | Excellent: High melting point and retains strength at elevated temperatures. | Poor: Softens and loses strength significantly at moderately high temperatures (>200°C). |

| Thermal & Electrical Conductivity | Poor: Acts as a relative insulator for both heat and electricity. | Excellent: A superior conductor of both heat and electricity. |

Let CastMold Guide Your Decision

Navigating the trade-offs between materials, manufacturing processes, and cost can be challenging. As a one-stop die casting solution provider, CastMold has deep expertise in both aluminum and zinc alloys, from mold design and manufacturing to precision CNC machining and flawless surface finishing. We can help you select the ideal material and optimize your design for manufacturability and cost-effectiveness.

If you are looking for a reliable die casting partner for your next project, contact us today for a free quote and design review. Let our expertise bring your vision to life.

Aluminum Die Casting Services

Learn more about our aluminum high pressure die casting services in China.