Welcome to the CastMold technical blog. As the CastMold Technical Advisor, my goal is to peel back the curtain on the complex manufacturing processes that turn your brilliant designs into tangible, high-performance products. Of all the processes in modern manufacturing, few combine speed, precision, and complexity quite like High Pressure Die Casting (HPDC).

You see it every day. The lightweight aluminum housing of your laptop, the intricate zinc-alloy connector in your phone, and the massive, single-piece structural underbody of a modern electric vehicle—all are marvels of HPDC.

But what is this process? How does it work? And most importantly, how do you, as an engineer, designer, or purchasing manager, leverage its power while avoiding its pitfalls?

This is not a brief overview. This is an engineer’s deep dive. We will cover the core physics, the four-stage cycle, the critical differences between machinery, the science of the alloys, and the “Design for Manufacturability” (DFM) rules you must follow for a successful part. At CastMold, this isn’t just theory; it’s our daily practice. We navigate these complexities—from aluminum and zinc die casting to in-house mold manufacturing and precision CNC finishing—to deliver your parts on time and to spec.

Let’s get started.

- What Is HPDC—and Why Use It?

- The HPDC Process Cycle: A Four-Stage of Production

- The Core Physics: Mastering the 3 Key Process Parameters

- The Machinery: Hot Chamber vs. Cold Chamber

- Materials Science: Choosing the Right Alloy for Your Part

- The Tool: Anatomy of an HPDC Die

- Quality Assurance: A Practical Guide to HPDC Defects

- HPDC in Context: How It Compares to Other Processes

- Conclusion: CastMold as Your End-to-End HPDC Partner

- Ready to Start Your Next Project?

- Aluminum Die Casting Services

What Is HPDC—and Why Use It?

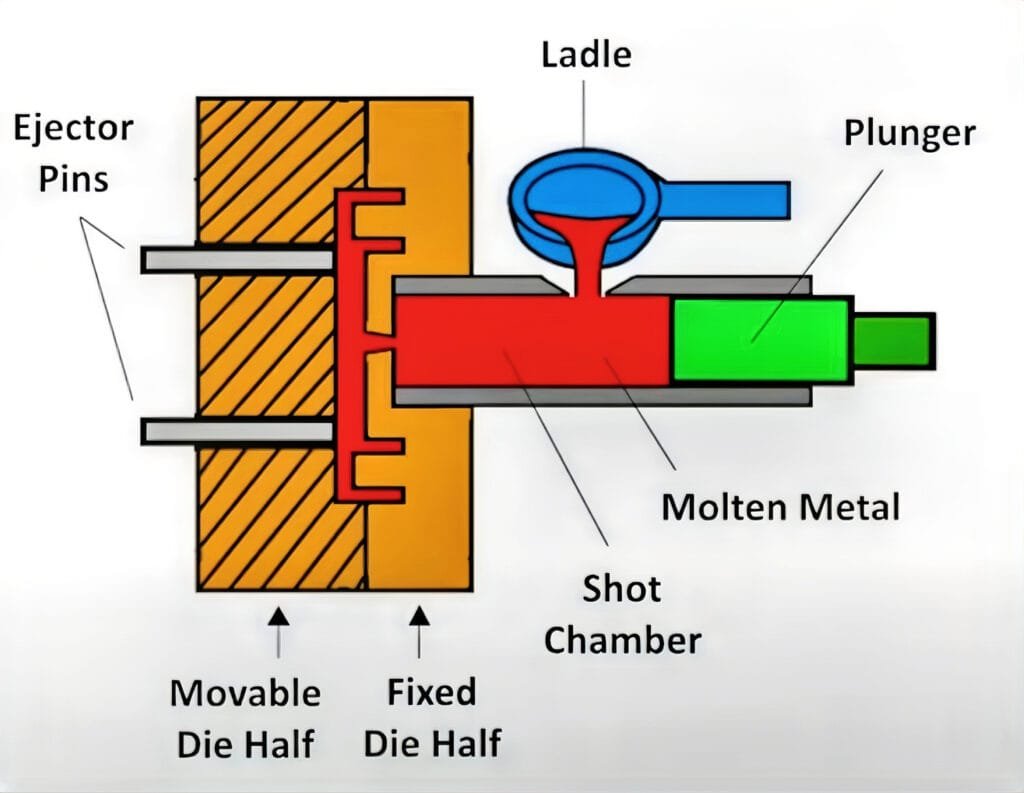

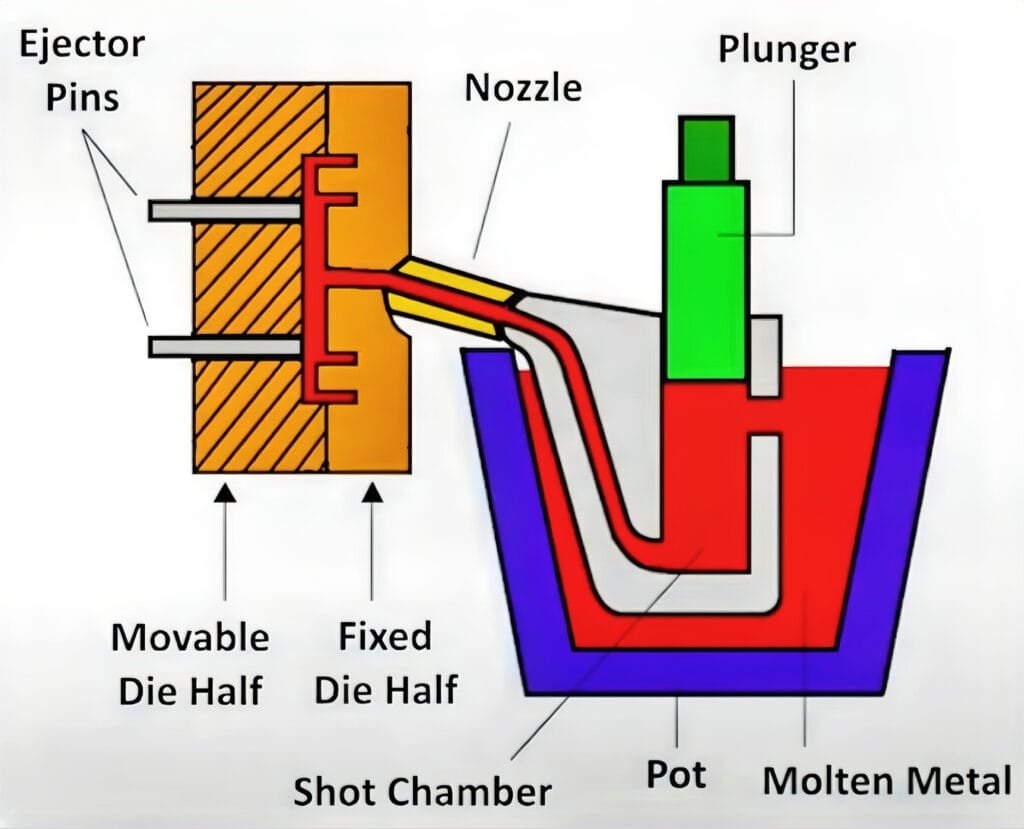

HPDC (High Pressure Die Casting) is a near-net-shape process where molten metal is injected into a hardened steel mold at high speed (tens of m/s) and solidifies under pressure. In cold-chamber HPDC (typical for aluminum), metal is ladled into a shot sleeve; a plunger drives the metal through the runner into the die. In hot-chamber HPDC (typical for zinc), the injection unit is immersed in the melt.

The Core Paradox of HPDC

This process is built on a fascinating engineering paradox.

- The Advantage: The extremely high-speed injection is what allows HPDC to produce incredibly complex parts with very thin walls (down to 0.40 mm), as the metal fills the entire cavity before it can prematurely solidify.

- The Disadvantage: This same high-speed, turbulent flow is the direct cause of its most significant challenge: porosity. Air and gases are unavoidably trapped during this violent fill.

Therefore, the entire process is engineered as a two-part system: a high-speed, defect-inducing fill, followed by a high-pressure, defect-mitigating compression. This “intensification” phase, which we’ll cover, is an essential countermeasure to the physics of the fill.

This balance defines the pros and cons you must consider:

Advantages:

- High Efficiency: Capable of high-volume, automated production.

- Complex Geometry: Produces intricate parts with thin walls that other processes can’t match.

- Accuracy & Finish: Delivers excellent dimensional accuracy and a smooth surface finish, reducing the need for secondary machining.

- Inserts: We can easily cast-in inserts, like steel screws or bushings, to simplify assembly.

Disadvantages:

- Porosity: An inherent risk of internal gas porosity, which must be managed.

- Alloy Limits: Mostly restricted to non-ferrous alloys (aluminum, zinc, magnesium).

- High Tooling Cost: The steel dies are complex and expensive, making HPDC cost-effective only for high-volume production.

Part Size: While “Giga-casting” is changing this, machines have size limitations.

The HPDC Process Cycle: A Four-Stage of Production

To understand HPDC, you must understand its cycle. This entire sequence is a meticulously orchestrated event, optimized for speed and repeatability. A complete cycle, from injection to ejection, can take anywhere from a few seconds for a small zinc part to a few minutes for a large aluminum casting.

Stage 1: Die Preparation and Clamping

Before any metal is injected, the die must be prepared.

- Cleaning: The die faces are cleaned of any residue from the previous cycle.

- Lubrication: The die cavities are sprayed with a lubricant or die release agent. This lubricant is critical: it creates a barrier to prevent the hot aluminum or zinc from adhering (soldering) to the steel die, and it also helps manage the surface temperature of the tool.

Clamping: The two halves of the die—the fixed (cover) half and the moving (ejector) half—are brought together and locked by the die casting machine’s clamping unit. This unit must generate a clamping force sufficient to withstand the massive injection pressure that’s about to come. Commercial machines can offer clamping forces exceeding 4,000 tons. This force calculation is a critical engineering step: it’s based on the total projected area of the part and its runner system, multiplied by the injection pressure.

Stage 2: The Multi-Phase Injection

This is the heart of the process, often occurring in a fraction of a second. It is not a single push, but a carefully controlled three-phase sequence.

- Phase 1 (Slow Shot): The injection plunger begins to advance at a low speed. This gently pushes the molten metal through the “shot sleeve” until it reaches the “gate”—the entry point to the die cavity. This controlled first phase is crucial for expelling air from the sleeve and minimizing turbulence before the metal enters the part cavity.

- Phase 2 (Fast Shot): The instant the molten metal passes the gate, the plunger accelerates to an extremely high velocity (30-100 m/s). This high-speed phase fills the entire die cavity in milliseconds, often under 100 ms. This incredible velocity is what ensures the metal reaches the furthest, thinnest extremities of the part before it can solidify.

- Phase 3 (Intensification): Immediately after the cavity is 100% full, a final, intense burst of pressure is applied to the molten metal. This intensification pressure, often exceeding 1,000 bar (100 MPa), is the solution to the “core paradox.” It performs two critical jobs:

- It compresses any residual gases that were trapped during the turbulent fast-shot phase, significantly reducing the size and effect of gas porosity.

- It forces additional molten metal into the cavity to compensate for the volume reduction (shrinkage) that occurs as the metal cools and solidifies

Stage 3: Solidification Under Pressure

Once injected, the molten metal cools and solidifies almost instantly upon contact with the relatively cool steel die surfaces. The die itself is a complex heat exchanger, with intricate internal water or oil cooling channels to manage this thermal load.

The cooling rates in HPDC are exceptionally high, ranging from 100 to 1000 K/s. This rapid solidification, all happening under the sustained pressure of the intensification phase, is what creates a fine-grained, dense microstructure in the final casting. This fine grain structure is a key reason why die-cast parts have high hardness and tensile strength compared to slower casting methods.

Stage 4: Ejection and Post-Casting Shakeout

After the casting has fully solidified (a matter of seconds), the clamping unit opens the die. The casting is intentionally retained in the moving (ejector) half.

A system of ejector pins is then hydraulically actuated, pushing the finished casting out of the die cavity.

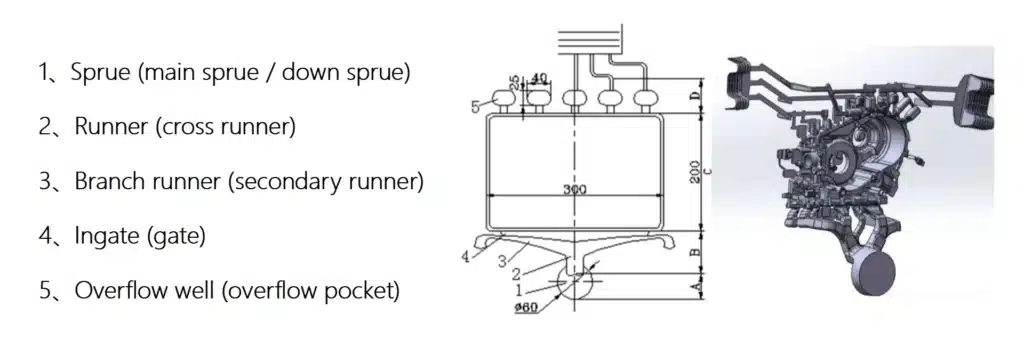

The part is not yet finished. It is still attached to the excess material from the runner system, gates, overflows, and any “flash” (thin metal that may escape the parting line). This entire “shot” is then moved to a trim press, where a trim die shears off the excess material in a single, clean step. The casting moves on to secondary operations (like CNC machining or surface finishing), and the trimmed scrap metal is remelted and recycled.

The Core Physics: Mastering the 3 Key Process Parameters

A successful HPDC part isn’t made by luck. It’s the result of precisely controlling the complex physics of the process47. At CastMold, our engineers are experts in dialing in the “big four” process parameters for every unique part geometry.

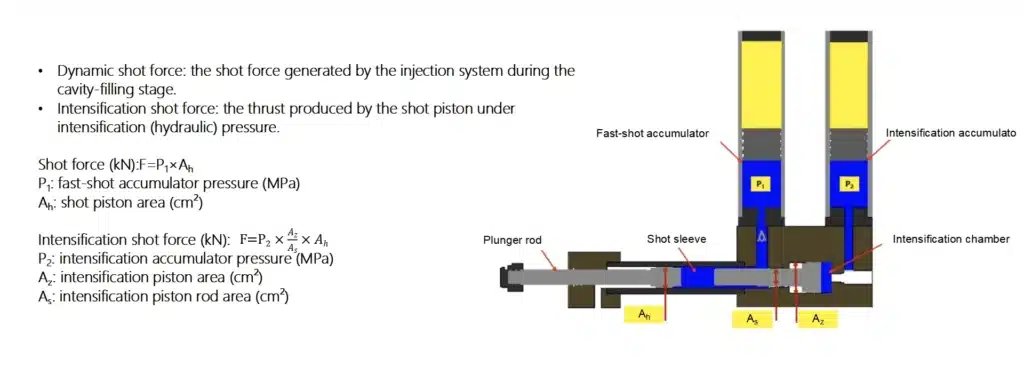

1. Pressure (Injection, Intensification, and Clamping)

Pressure is everything. We manage three distinct types:

- Injection Pressure (P1): This is the pressure from the machine’s hydraulic system (accumulator) that drives the plunger forward during the fast shot.

- Intensification Pressure (P2): This is the final squeeze applied after the fill. We calculate and set this “specific intensification pressure” based on the alloy and the part’s requirements. A simple cover might need 400 bar, but a pressure-tight, structural component may require over 1,000 bar to minimize porosity.

- Clamping Force (Fm): As discussed, this is the reaction force. It must be greater than the total separating force, which is the injection pressure multiplied by the total projected area of everything in the die (part, runners, overflows). This is a non-negotiable calculation to prevent flash.

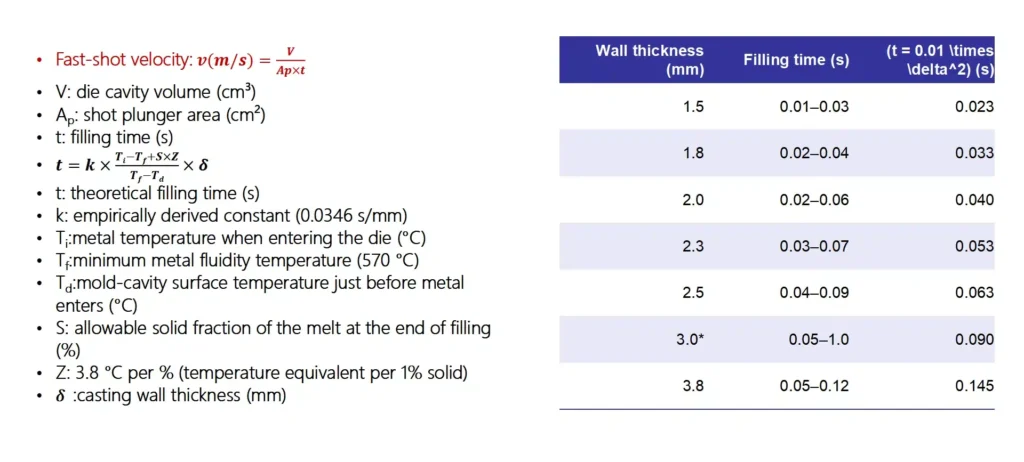

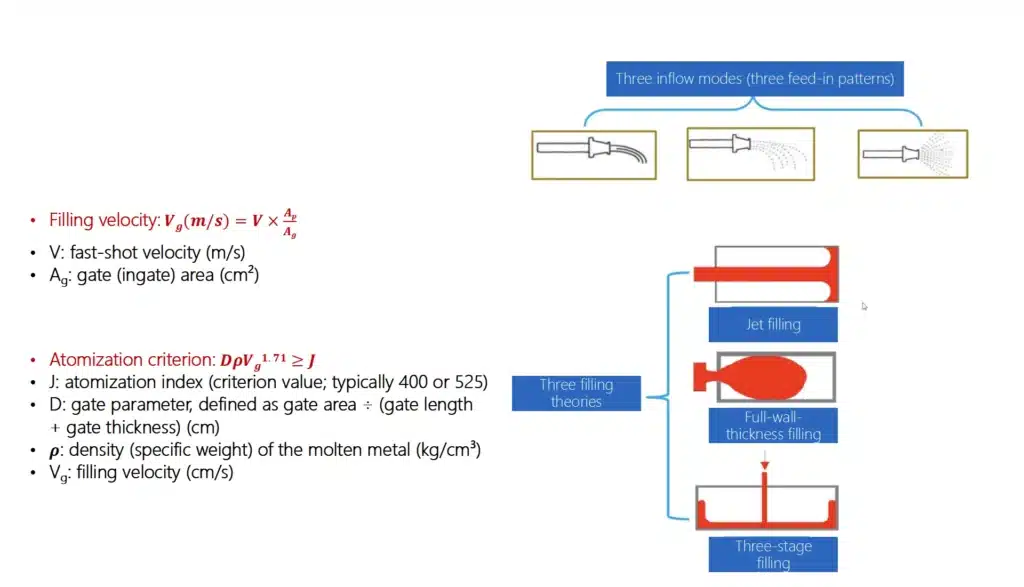

2. Speed (Slow Shot, Fast Shot and Filling)

Speed is arguably the most complex parameter to control. It’s not one speed, but a “velocity profile” that changes based on the plunger’s position.

- Slow Shot Speed (Vs): The speed of the plunger as it pushes metal through the sleeve. We calculate this speed based on the “fill percentage” of the sleeve to ensure air is smoothly expelled, not churned into the metal.

- Fast Shot Speed (Vf): The critical speed that determines the Filling Time. The filling time is the target. It’s calculated based on the part’s wall thickness, alloy temperature, die temperature, and solidification properties. A thin-walled part (e.g., 1 mm) may require a fill time of just 20 milliseconds, while a thicker part (e.g., 5 mm) might allow 100 milliseconds.

- Gating Velocity (Vg): This is the actual speed of the metal as it enters the part cavity. It’s a function of the fast shot speed and the die design. Our engineers design the gates to achieve an optimal velocity (e.g., 30-60 m/s) to fill the part completely without causing atomization or excessive erosion.

| Wall thickness (mm) | Filling velocity (m/s) |

|---|---|

| ≤ 0.8 | 46–55 |

| 1.3–1.5 | 43–52 |

| 1.7–2.3 | 40–49 |

| 2.4–2.8 | 37–46 |

| 2.9–3.8 | 34–43 |

| 4.6–5.1 | 32–40 |

| ≥ 6.1 | 28–35 |

3. Temperature (Alloy vs. Die)

HPDC is a thermal balancing act. We manage a massive thermal gradient between the molten metal and the steel die.

- Alloy Pouring Temperature: This is set based on the alloy, wall thickness, and part complexity. For example, an A380 aluminum alloy for a complex, thin-walled part might be poured at 660-680°C. Too hot, and you risk “soldering” (welding) the part to the die and increase cycle time. Too cold, and you get “cold shuts” or misruns.

- Die Temperature: This is the most misunderstood parameter. The die is not cold. It is pre-heated to a stable operating temperature (e.g., 220-300°C for aluminum) and maintained there by an intricate network of internal heating and cooling channels. A stable die temperature is essential for controlling solidification, ensuring dimensional stability, and (most importantly) prolonging the life of the expensive tool.

| Alloy | Casting wall ≤ 3 mm — Simple | ≤ 3 mm — Complex | > 3 mm — Simple | > 3 mm — Complex |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zinc alloys | 420–440 | 430–450 | 410–430 | 420–440 |

| Aluminum alloys (Si-bearing) | 610–650 | 640–700 | 590–630 | 610–650 |

| Aluminum alloys (Cu-bearing) | 620–650 | 640–720 | 600–640 | 620–650 |

| Aluminum alloys (Mg-bearing) | 640–680 | 660–700 | 620–660 | 640–680 |

| Magnesium alloys | 640–680 | 660–700 | 620–660 | 640–680 |

| Copper alloys — Common brass | 870–920 | 900–950 | 850–900 | 870–920 |

| Copper alloys — Silicon brass | 900–940 | 930–970 | 880–920 | 900–940 |

| Alloy | Parameter | Casting wall ≤ 3 mm — Simple | ≤ 3 mm — Complex | > 3 mm — Simple | > 3 mm — Complex |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zinc alloys | Preheat temperature | 130–180 | 150–200 | 110–140 | 120–150 |

| Continuous operating / holding temperature | 180–200 | 190–220 | 140–170 | 150–200 | |

| Aluminum alloys | Preheat temperature | 150–180 | 200–230 | 120–150 | 150–180 |

| Continuous operating / holding temperature | 180–240 | 250–280 | 150–180 | 180–200 | |

| Al-Mg alloys | Preheat temperature | 170–190 | 220–240 | 150–170 | 170–190 |

| Continuous operating / holding temperature | 200–220 | 260–280 | 180–200 | 200–240 |

The Machinery: Hot Chamber vs. Cold Chamber

The machines that execute this process come in two main flavors: hot chamber and cold chamber. The choice between them is dictated almost entirely by the melting point and chemical properties of the alloy you want to cast.

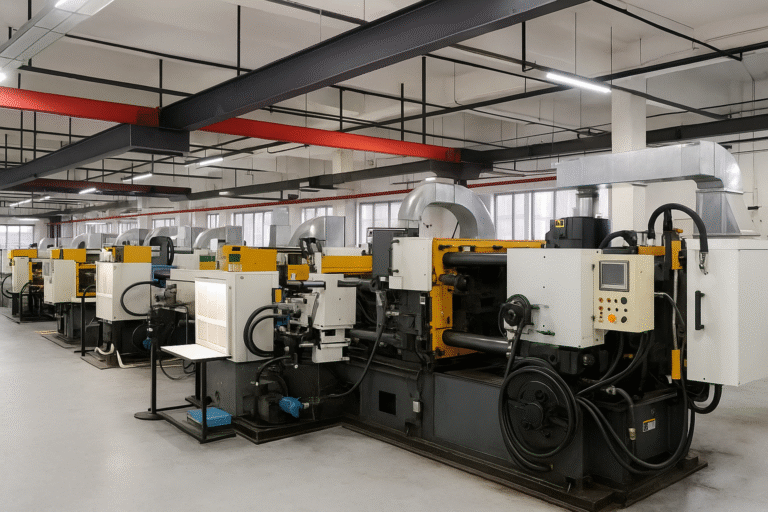

At CastMold, we are masters of both, allowing us to select the perfect process for your material.

Cold Chamber Machines (For Aluminum & High-Temp Alloys)

This is the workhorse for high-melting-point alloys like aluminum, magnesium, and copper.

- Mechanism: The melting furnace is separate from the die casting machine.

- Process: For each cycle, a precise amount of molten aluminum is transferred (typically by an automated ladle) from the furnace into the machine’s “cold chamber” or shot sleeve. A hydraulic plunger then pushes this “shot” of metal into the die.

- Why? This design is a direct engineering solution to a material science problem. High-temperature molten aluminum is extremely corrosive72. If the injection components were continuously submerged (like in a hot chamber machine), the aluminum would quickly dissolve the steel plunger and gooseneck.

- CastMold’s Application: This is the process we use for all our aluminum alloy die casting, including A380, ADC12, and AlSi12 components. It’s ideal for producing robust parts, from electronic enclosures to large automotive structural components.

- Trade-off: Cycle times are slower (e.g., 50-90 shots per hour) because of the extra ladling step.

Hot Chamber (Gooseneck) Machines (For Zinc & Low-Temp Alloys)

This process is designed for speed and efficiency, but is limited to low-melting-point, non-corrosive alloys.

- Mechanism: The furnace containing the molten metal is integral to the die casting machine.

- Process: The injection mechanism, which includes a “gooseneck” and a plunger, is submerged directly in the molten metal bath. To inject, the plunger simply moves down, forcing metal up the gooseneck and into the die.

- Alloys: This is the exclusive domain of zinc alloys (Zamak), tin, and lead.

- CastMold’s Application: This is our chosen process for all zinc alloy die casting, such as Zamak 3 and Zamak 5. The low casting temperature of zinc is not corrosive to the submerged steel components.

Advantage: This process is exceptionally fast. With no ladling step, cycle rates of 400-900 shots per hour are common, making it ideal for mass-producing small to medium-sized precision parts.

Materials Science: Choosing the Right Alloy for Your Part

The alloy you choose dictates everything: the machine, the die temperature, the final part’s properties, and the cost. HPDC is almost exclusively limited to non-ferrous metals because the high temperatures of molten steel would destroy the die.

| Property | Zinc alloy | Aluminum alloy | Magnesium alloy | Copper alloy | Cast steel |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical & chemical properties | |||||

| Melting temperature | 5 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Density | 3 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 2 |

| Electrical conductivity | 3 | 5 | 3 | 1 | — |

| Thermal conductivity | 3 | 1 | 2 | 4 | — |

| Corrosion resistance | 3 | 4 | 2 | 4 | — |

| Mechanical properties | |||||

| Tensile strength | 3 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 5 |

| Yield strength | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Elongation | 3 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 5 |

| Impact toughness | 3 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 5 |

| Casting characteristics | |||||

| Fluidity | 5 | 1 | 4 | 3 | — |

| Cracking tendency | 5 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| Soldering/sticking-to-die tendency | 5 | 3 | 5 | 4 | — |

| Minimum wall thickness | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | — |

Aluminum Alloys

| System | JIS | GB/T | AA (US) | Typical profile |

| Al-Si | ADC1 | YL102 / YZA/Si12 | A413.0 | Best castability; lower mechanicals; good fluidity and pressure tightness with process control. |

| Al-Si-Mg | ADC3 | YL101 / YZAlSi10Mg | A360.0 | Higher impact and yield vs ADC1; slightly less castability than pure Al-Si. |

| Al-Mg | ADC5 | YL302 / YZAlMg5Si1 | 518.0 | Best corrosion resistance; good elongation; castability lower than Al-Si. |

| Al-Mg-Mn | ADC6 | 515.0 | Similar to ADC5 with improved ductility; castability a touch better. | |

| Al-Si-Cu | ADC10 | YL112 / YZAlSi9Cu4 | A380.0 | “Workhorse” alloy; balanced strength/machinability/castability. |

| Al-Si-Cu | ADC12 | YL113 / YZAlSi11Cu4 | A383.0 | Improved fluidity over A380; widely used for thin-wall parts. |

| Al-Si-Cu-Mg | ADC14 | YL117 / YZAlSi17Cu5Mg | B390.0 | Very high wear resistance and fluidity; low elongation. |

- Iron (Fe): improves die-casting performance (anti-soldering to the die); increases mechanical strength, lowers elongation.

- Silicon (Si): improves castability; increases strength and wear resistance; reduces the coefficient of thermal expansion.

- Manganese (Mn): enhances anti-soldering performance; suppresses formation of needle-like β-Fe phase.

- Copper (Cu): increases strength and elastic modulus but reduces corrosion resistance; improves high-temperature mechanical properties (creep resistance).

- Magnesium (Mg): increases alloy strength; reduces hot-cracking tendency.

- Strontium (Sr): effectively modifies eutectic silicon, improving toughness.

For high-strength, high-toughness alloys

- Si: ensure good castability/formability.

- Fe (~0.15%): control formation of needle-like Fe phases to maintain toughness.

- Mn: use Mn in place of Fe to improve die release (anti-soldering).

- Mg: broad usable range; adjust content according to required properties.

- Sr: modify eutectic Si so that, after heat treatment, the silicon spheroidizes well, improving toughness.

Zinc Alloys (e.g., Zamak 3, Zamak 5)

When precision, thin walls, and surface finish are your top priorities, zinc is the answer.

- Properties: Zinc alloys are prized for their superior casting characteristics. They have the lowest melting point and exceptional fluidity, allowing for the casting of parts with extremely thin walls (down to 0.35 mm) and intricate features with very tight tolerances. Zinc is, by far, the easiest alloy to cast.

- Key Benefit: The low casting temperature (400-425°C) puts very little thermal stress on the die. This means die life is significantly longer—often 5-10 times longer than a die for aluminum—which can dramatically lower the long-term per-part cost.

- Finishing: Zinc castings have an inherently smooth, high-quality surface finish, making them the ideal substrate for post-processing like plating, painting, and chromating.

- Applications: Automotive interior parts, decorative hardware (handles, faucets), and electronic connectors and housings (where its weight provides a high-quality feel and excellent EMI shielding).

Magnesium Alloys (e.g., AZ91D)

When absolute minimum weight is the primary design driver, magnesium is the material of choice.

- Properties: As the lightest of all common structural metals, magnesium is 33% lighter than aluminum. It offers the highest strength-to-weight ratio, plus excellent EMI shielding and vibration damping.

- Trade-offs: It comes at a higher material cost than aluminum and is generally softer. It also requires special handling (like a protective cover gas) when molten to prevent oxidation and fire.

- Applications: Housings for portable electronics (laptops, cameras), automotive components (steering wheel frames, instrument panels), and aerospace parts.

The Tool: Anatomy of an HPDC Die

The die casting die is not a simple mold. It is an active, highly engineered piece of machinery that must withstand extreme thermal and mechanical shock for hundreds of thousands of cycles. The high cost and complexity of this tooling are defining features of the HPDC process.At CastMold, our in-house tool shop designs and builds these dies, giving us full control over the quality and timeline of your project. A typical die is built from high-quality H13 tool steel and comprises two halves: the stationary (cover) half and the moving (ejector) half.

Key features include:

- Die Cavity: The precision-machined void that forms your part’s shape. This is often made as a separate insert from premium tool steel, which is then fitted into a larger “moldbase” or holder.

- Runner & Gates: The channel network that transports molten metal from the shot sleeve to the die cavity. The gate is the specific entry point, and its design (size, location, angle) is critical for controlling flow velocity and quality.

- Vents & Overflows: Vents are paper-thin channels (e.g., 0.1-0.2 mm) that allow trapped air and gases to escape the cavity during the high-speed fill110. Overflows are small pockets designed to capture the initial, colder metal front, ensuring hot metal fills the part.

- Ejector Pins: The system of hardened pins that pushes the finished casting out of the die after solidification.

- Cores & Slides (for Undercuts): These are the most complex features. If your part has a feature that can’t be formed by the two main die halves (like a hole on the side), it requires a movable slide or core. These mechanisms are hydraulically or mechanically actuated to move into place, form the feature, and then retract before the die opens, allowing the part to be ejected. Slides add significant complexity and cost to a tool, which is why we address them first in our DFM analysis.

Quality Assurance: A Practical Guide to HPDC Defects

Even in a highly controlled process, defects can occur. Understanding their root causes is the key to prevention. This is where our quality assurance and process control teams shine.

The Primary Challenge: Porosity (Gas vs. Shrinkage)

Porosity is the most common and persistent defect in HPDC, manifesting as internal voids that can compromise strength and pressure tightness. It comes in two forms:

Gas Porosity:

- Appearance: Smooth-walled, spherical voids.

- Cause: Trapped air from the turbulent fill, or gasses from vaporized die lubricant.

- Prevention: Optimized injection profile (especially the slow shot), ensuring die vents are clean and effective, and, for critical parts, using Vacuum-Assisted HPDC to evacuate air from the die before injection.

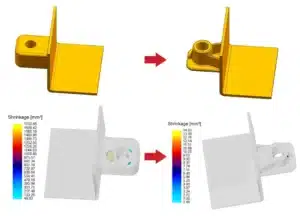

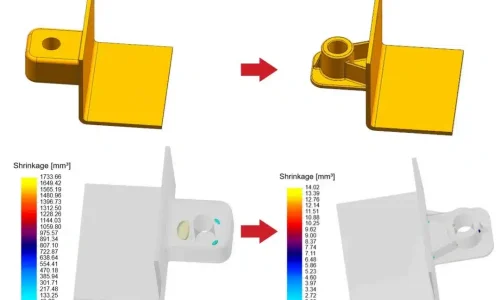

Shrinkage Porosity:

- Appearance: Jagged, irregular-shaped voids, often in thick sections.

- Cause: Insufficient molten metal to feed a section as it cools and contracts. This is the direct result of “hot spots” caused by non-uniform wall thickness.

- Prevention: Good DFM is the #1 cure (uniform walls!). Also, effective die thermal management and applying sufficient intensification pressure to force-feed these shrinking regions.

Flow-Related Defects

Cold Shuts: These appear as lines or cracks on the surface where two fronts of molten metal met but were too cool to fuse together completely.

- Cause: Low molten metal temperature, low die temperature, or insufficient injection speed.

- Prevention: Increase metal or die temperatures, or increase the fast shot speed.

Misruns: An incomplete part where the metal solidified before filling the cavity.

- Cause: Similar to cold shuts—temps are too low, or injection speed/pressure is insufficient.

Flow Marks: Wavy patterns on the casting surface.

- Cause: Variations in the flow front, temperature differentials on the die, or improper/excessive lubricant spray.

Die-Related Defects

Flash: A thin web of excess metal forced out of the die at the parting line.

- Cause: Insufficient machine clamping force, worn or damaged die surfaces, or excessive injection pressure.

- Prevention: Using the correct clamping force calculation (Fm) and regular die maintenance.

Soldering: A severe defect where the molten alloy (especially aluminum) chemically welds itself to the steel die surface. This damages the part upon ejection and rapidly destroys the tool.

- Cause: Excessive die temperatures, breakdown of the protective lubricant layer, or the wrong alloy chemistry (e.g., too little iron in aluminum).

- Prevention: Strict thermal control of the die and a consistent, high-quality lubrication process.

HPDC in Context: How It Compares to Other Processes

To know if HPDC is right for you, you need to see where it fits in the manufacturing landscape.

HPDC vs. Gravity Die Casting (GDC) & Low-Pressure Die Casting (LPDC)

The key difference is the fill method.

- GDC uses only gravity.

- LPDC uses low, controlled air pressure (0.7–1.5 bar).

- HPDC uses a high-speed ram (up to 1500+ bar).

This leads to a clear trade-off:

- HPDC offers the fastest production rates and the best ability to make thin-walled, complex parts. However, the turbulent fill creates high porosity, which generally means parts cannot be heat-treated (trapped gas expands and blisters the part).

- GDC and LPDC have a gentle, non-turbulent fill. This results in parts with very low porosity and a sounder structure. These parts can be heat-treated for superior mechanical properties. The trade-off is a much slower cycle time and an inability to cast very thin sections.

- Cost: HPDC has the highest machine and tooling costs, making it ideal for high volumes. GDC has the lowest tooling cost, suiting it for lower volumes.

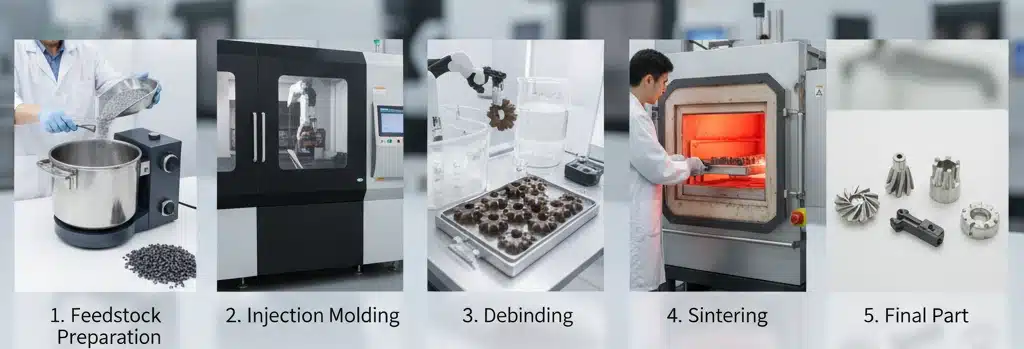

H3: HPDC vs. Metal Injection Molding (MIM)

These processes seem similar but are fundamentally different.

- HPDC injects molten metal.

- MIM injects a feedstock of fine metal powder mixed with a polymer binder. The “green” part is then put through a “debinding” process to remove the binder, followed by “sintering” at high temperatures, where the metal particles fuse into a dense solid.

The difference is clear:

- Materials: MIM can process a far wider range of materials, including stainless steels, tool steels, and titanium, which cannot be die cast.

- Complexity & Size: MIM excels at producing very small (<100g), extremely complex parts with exceptional precision, often eliminating all secondary machining. HPDC is better suited for medium to very large components.

- Properties: A final MIM part is very dense (>95%) and has mechanical properties that can approach wrought metals. HPDC parts are strong, but have inherent porosity.

- Cost: Both have high tooling costs, but MIM’s raw material (fine metal powder) is significantly more expensive, making it best for high-volume, small, high-value parts.

Conclusion: CastMold as Your End-to-End HPDC Partner

High Pressure Die Casting is a cornerstone of modern manufacturing, defined by its ability to produce complex, near-net-shape metal parts with exceptional speed. As we’ve seen, it is a process of sophisticated engineering trade-offs: speed vs. turbulence, material chemistry vs. machine type, and part design vs. the physics of solidification.

Success is not an accident. It is the result of mastering this complex system.

Understanding this entire process—from an initial DFM analysis and alloy selection to the design of the tool, the precise control of the casting parameters, and the final CNC machining and finishing—is what we do every day.

We are not just a supplier. We are your technical partner, ready to help you navigate these challenges and turn your design into a high-quality, production-ready component.

Ready to Start Your Next Project?

The engineering team at CastMold is here to help. We provide a one-stop solution for all your die casting needs, from aluminum and zinc casting to in-house mold making, precision CNC machining, and high-quality surface finishing.

Contact us today for a free DFM analysis and a comprehensive quote. Let us show you how we can optimize your design, reduce your costs, and be your reliable partner for high-volume manufacturing.

Aluminum Die Casting Services

Learn more about our aluminum high pressure die casting services in China.